Glutton for Punishment: The First Contract

- Tuna

- Sep 30, 2016

- 18 min read

We obtained our first cargo contract going from SEA-KTN-YAK. I am grateful that we are finally getting out of Seattle due to the swollen fees that have accumulated at this airport. Unfortunately, this is one of the most expensive airports we operate in.

The airplane was readied the night before by our trusty mechanic Joe. We picked Joe up from Ketchikan from a friend’s referral. I am glad we have got him. It seems as though Joe has worked on everything with wings especially the classic jets. He has a history with Alaska Airlines working on the -200 right before they retired them. You may say he uses “the force” with the airplane and knows what’s wrong with her before the issue arises.

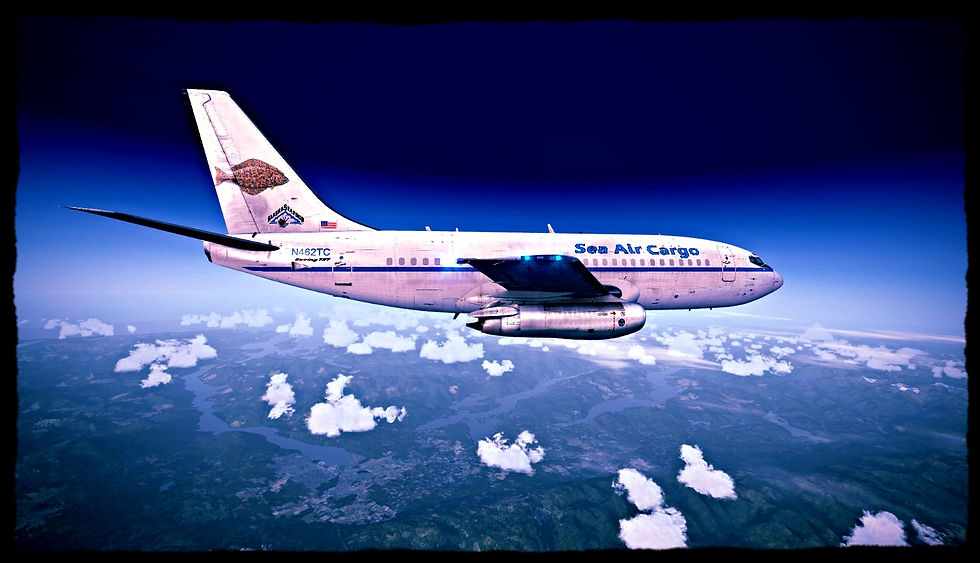

N462TC was re-painted, well not so much re-painted but they slapped a blue strip and our companies’ logo on the tail. The re-paint shop wanted north of $150,000 dollars to re-paint the plane. There is no way that was going to happen. We need to keep all the funds we have and not waste it on white paint. So we struck a deal with the total cost of $50,000 out the door. It’s a good thing that the plane was white to begin with. I think we got away with a good deal.

All of the planning was worth our first contract. We were able to secure about 21000 LBS of cargo going to KTN and then YAK, although I am not certain on the amount we grossed yet, I think we made a small profit. I will have better figures a bit later when the bills come in.

Dawns First Light

Approaching the cargo ramp at SEA we were parked at stand R1 in the cargo area. Joe was already looking at the APU as it was acting up a bit in the previous day’s inspections. Mike and I checked in at the counter and I went to look at the weather forecast for our route. I took a look at the WSI forecast packet and the TAF was dismal to say the least. At our time of arrival it was going to be 2SM in mist and 300 overcast. I took a peak at the charted minimums which were ½ and 300 ceilings. If the weather held up to forecast, it was going to be a hard approach in the soup with minimums to boot. The only good news was that the weather was to improve to 6SM overcast layer at 8,000. But that would not be until five hours after arrival.

Mike was next to me and I showed him the forecast, “take a look at the forecast, 300 and two with a cold front approaching.” I slid the paperwork toward him and looked at his expression for any signs of concern.

Mike looked at the weather with no expression at all and said, “Well, let’s not screw up the approach then.” Mike was from the South and his southern drawl was comforting. Mike had the misfortune for helping us out with this cargo startup. He was instructing and flying corporate folks all over the Southern states before coming up to work for me. He and I were college buddies and has almost killed me in an airplane about fives before, so I figured it was time for him to payback the debt.

We choose Juneau as an alternate and added about 20 minutes of holding fuel just in case. The weather was going to be a bit better in Juneau, but one thing is for certain…this is Alaska and weather turns bad to worse in a few tics on the clock. When it was all said and done we took about 23,300 pounds of fuel with an arrival fuel of just about 13,100 pounds at Ketchikan. That would give us around two hours of fuel to play with. We factored in 20 minutes of holding fuel before we needed to get out of dodge and plan an alternate. I looked over the figures and the flight plan, this would be a VOR to VOR type flight with no GPS installed on this bird. Matter of fact, my smart phone has more computing power then this old dinosaur.

The Rampers

Mike and I walk out onto the cargo ramp after scanning our badges and going through the normal TSA security screening. It seems as there is no way of saving time no matter what you end up flying. As we approached the airplane Joe was just buttoning up the APU cowl. I looked at Mike and stated “Why don’t you go to the flight deck and get the thing warmed up, and I will load the cargo?” I didn’t want Mike responsible for damaging the airframe on the first revenue flight. I got into the ULd loader and looked over the manifest, there was a cargo ramp agent waiting for me to sign over the paperwork. He seemed a bit rushed and was looking for someone somewhere on the ramp.

“This is it?” I asked. I looked over the cargo ULDs. We have an uplift of 21,000 pounds of cargo.

“Yup that’s it, 21,000 pounds all to Alaska, first three are to Yakutat and the last four to Ketchican.” I thank him and he went looking for someone on the radio he was carrying.

I loaded the Yakutat cargo first, as this would be our last stop. The loading process went well as expected with no major issues to report.

I conducted a walk around trying to inspect the aircraft as normal. The issue is that this thing has 63,000 cycles and about that much in hours, so things will tend to break on occasion. Joe was standing by engine number one, “Hey how does she look?” I asked.

“Looks great, I don’t see any major issues, I just top off the oil and checked the hydraulics, wheel-well is in good shape covered with a film of hydraulic oil.” He said.

I looked at him with a puzzled expression, “Wait what? It’s covered with hydraulic oil? I just looked in there!” I said.

Joe looked at me and said, “If there ain’t no hydraulic oil in the wheel-well then she is out of hydraulic.” Joe smirked and smiled.

“Very funny Joe,” I said, “I am sure glad you’re coming along on this flight as you’ll be hanging on for dear life thinking if you put this thing back together correctly.” The smile went away and deep thought pursued.

“See ya on board,” I said with a smile on my face. I climbed up the stairs to find Mike in the galley trying to make a pot of coffee.

“This dang coffee pot ain’t worth two dead flies on a horse,” Mike stated in frustration. I looked at him and said, “Go down to the cargo lounge area where the crew area is, there has got to be some down there.”

“Nope, I want to get this thing rolling, I will make a pot airborne.” Mike said in a defeated tone.

I ducked my head under the overhead panel of the aircraft and put my flight case on the jump-seat and pulled out my I-pad Air. I clamped it to my Pivot mount on the left side window and secured the housing. I put my flight case on the left side floor area where Mr. Boeing has built a compartment for these things. The airplane was alive and breathing it seemed. There is something about the classics that I have grown to love. There is a constant clack, clack, clack, clack, clack, noise from the flight deck that only a 737 pilot would know. It’s generated by the instrumentation of the cooling fans and such a comforting sound.

While I was standing up I reached over and pushed the leading edge flaps test button, checked the crew oxygen and passenger oxygen and test both mach airspeed warning tests, followed by the stall warning test and flipped on the dome lighting. I ducked under the overhead panel and climbed over the pedestal panel to jam myself into a sheep skinned comfortable seat. This is a 737, so the flight deck felt as cramped a Cessna 152 with a hefty flight instructor sitting next to you. There is not a lot of room to maneuver in these flight decks, unlike the Airbus style where you get to prop a nice desk up and do the crosswords on your latest Airways magazine. No such way that is going to happen in the guppy. However, I felt right at home in this dinosaur and knew the sounds and smells well here.

I took out the dispatch paperwork and handed it to Mike. Mike reached across the throttles and started to punch in the data on the PDCS, which was located on my bottom right knee area. I could tell it was a bit of a stretch for him to enter in the data, but I needed to complete the captain’s duties which were located mostly on the overhead panel. This was to be my leg flying so I was the pilot flying which meant more items for me to check than the average guy. The process went extremely efficient having done these thousands of times on the newer type 737. There were just a few oddball items that the newer aircraft do not have, like generator temperatures, pressurization panel, and a few other items. This process took about fifteen to twenty minutes to complete and Mike was completed on the data and was just finishing up his duties on the right side overhead panel.

Picking up the paperwork in my right hand I looked at the data and backed up Mike’s work to ensure there were no mistakes in the data entry phase. “Mike, back me up on the overhead to ensure that I did not miss anything on my end.”

“Yeah sure,” Mike responded. Mike was used to me being thorough. In college were flight partners and had to fly with each other four hours straight twice a week. The first time I met him, my flight instructor, who was a bit on the insane side told me to help Mike on the ramp do a pre-flight inspection. I walked outside and noticed Mike in the cockpit of our Cessna 172 listening to the ATIS report. I placed my flight bag by the left wing and introduced myself. “Hey are you Mike?” I asked.

“Yeah, you must be Jason,” his southern accent was deep and his attitude was infectious. I tend to do things by the book so to be paired up with this maniac was a bit of a stretch for me.

“Pete sent me out to help you with the preflight, have you done it yet?” I asked.

“Hold on,” Mike got out of the airplane and walked over to me by the left wing, he reached up grabbed the wing with his two hands and shook the crap out of airplane. He rocked it so hard that I heard the flight control cables banging onto the metal fuselage. He suddenly stopped, look at me and with his southern drawl said “Did you see anything fall off?”

“Nope,” I responded with utter shock on my face.

“Well let’s get-er done!”

It was from that point on I knew we were going to have a great adventure in our college career.

I finished checking the PDCS data and Mike was completed with the cross check. I heard Joe walking in and noticed that he started closing the big cargo door.

“Okay Mike let’s start the brief,” I stated.

“I am all ears, and I got the charts pulled up,” Mike said.

“Weather in Seattle is 350 at six, with ten miles visibility, few clouds at twenty five hundred, temp 16 dew-point 8, altimeter two-niner, niner seven. For abnormal and aborts, we will stop this thing on any indication under 80 knots. I will put the throttles to idle, full breaking, reverse thrust if needed and ensure that the speed-brake deploys. I will only abort on any kind of fire, engine failure, any wind-shear warning or if you’re screaming loudly above 80 knots. Runway is 34R with a long taxi on bravo to the runway. It’s about 11,900 feet and no contamination reported. No terrain issues, and a few threats here. Possible threats I see are latent instrumentation issue with regards to scanning the six pack. I have not flown a steam-style gage aircraft in quite a long time and therefore I may be a bit behind. Please back me up on the departure and call any abnormalities you may notice. Obviously birds are an issue here at this airport and we will plan on a return to 16L or 34R if we are stable. If we have a double flameout we’ll turn slightly to the right and plan for King County. The departure will be Seattle five straight out on a heading of 344, for vectors to ORCA, Any questions, concerns or cheap shots?”

Mike looked at me and said, “You have flown passenger aircraft for too long man, that was more like the D-day invasion plan.” I heard Joe now laughing as he was in the jump seat strapping in his harness.

“APU on, let’s burn this candle,” I said, not wanting the banter to continue at my expense. The ground crew was on the headset and asked if we were ready to go. We ran the checklist and corresponded to the ground crew with an affirmative.

I put two fingers in the air right on the glare-shield next to the main windscreen so the wing walker could see and made a twirling sign to indicate that I wanted to start the number two engine first. He looked and me and then at the engine, with one orange wand he pointed at the number two engine and with his free hand made a rotation gesture.

“Clear to start two,” I said. Mike reached up with his left hand turned the engine start switch to ground position after verifying adequate duct pressure. The start switch is held into position magnetically and when the starter cuts out the switch returns back to off.

I focused on the N2 gauge and watched the spool-up. If you have never started the JT8D engines the best way to describe the start-up noise is to picture a giant taking a nap and waking said giant up. It starts with a low moan and progressively gets to a higher pitch and then boom! The fuel is added and moan becomes a grown with a higher pitch to it.

I watched the EGT gauge steadily rise, this could be a hot start in which the fuel burns too soon and the engine does not have enough airflow through the turbine to cool it down. This results in a hot EGT and an immediate shutdown. The -200 is notorious for starting quick and the EGT can get out of hand if not watched. My hand was on the fuel cutoff waiting for the EGT to settle down.

Within a short time the EGT came down to normal limits as rollback occurred.

“Good start on two, let’s start one,” I said looking at Mike. I conducted the same procedure as the number two start with engine number one. I raised one finger on the glareshield and rotated it to alert the ground crew that I wished to start the number one engine. The wing walker signaled as before and Mike placed the engine starter switch to ground. Engine one started normal and we went through our after start flows. With flaps set to five we called Seattle ground and requested taxi clearance.

Pushing the throttles forward, I heard and felt the JT8D engines come to life with a high pitched wine that low bypass engines produce. We started to roll and I maintained the centerline of the taxiway using the nosewheel tiller. We taxied down bravo and were number three for takeoff.

Taxiing 462TC to 34R SEA

Number three for takeoff

“Halibut 8311 line up and wait runway three four right.” The tower controller sounded in our headsets.

Mike responded. “Rodger, line up and wait three four right, halibut 8311.”

I pushed the throttles up and guided the aging aircraft on the runway. This workhorse of a jet has seen many takeoffs and landings and here comes one more takeoff to add to the long career of this magnificent machine.

“Landing lights on, packs on, bleeds on, APU off, recall clear,” Mike read the takeoff checklist.

“Halibut 8311, winds three five zero at six, runway three four right, cleared for takeoff.”

Mike read back the takeoff instructions, I placed my hands on the throttles and pushed them to 40% N1. I let the engines stabilize and hesitated a few seconds. I then pushed them up to the takeoff EPR of 1.98. I was a bit surprised one how delayed the spool-up was. I am used to flying modern day 737’s with a higher bypass and a bit more responsive engines. I put the throttles close to 1.98 and let Mike adjust the remaining engine EPR to our preset levels.

The noise was loud and the acceleration was prompt. As we started accelerating down the runway, we felt all the bumps in the pavement as we started to bounce in our seats. I paid attention our airspeed indicator and noticed that the acceleration was normal and double-checked the power settings. We continued down the runway and our bodies were pressed back in our seats due to the acceleration force.

“Vee one,” Mike called followed by “Rotate.” I pulled the nose back and started to rotate toward takeoff attitude. We felt and heard a thump-thump, and became airborne soon after.

“Positive rate,” Mike stated.

“Gear-up,” I said after confirming that we achieved the necessary attitude and altitude. Mike placed his hands on the gear lever and retracted the gear.

Line up and waiting for takeoff

No time to think

Climb out was normal and we had to continuously adjust the throttles as there were no auto-throttles on this airplane. Keeping airspeed was challenging at best. To say this airplane was relaxing to fly is an understatement. The entire route we were busy with burn calculations, weight calculations, and time calculations. Aviating skill had to be exercised, so as to not be lost over Canada somewhere. We had to know exactly where we were at all times using ground-based navigational skills taught to us as student pilots. There is no magenta line here telling us where to go. This was done by traditional navigation and if felt good to be able to fly like they did in times past.

The terrain we flew over is simply stunning even at thirty-six thousand feet. We started over Vancouver, and then tracked just East over Vancouver Island on a North West heading. Two hours of flying seems as just a few minutes when flying this airplane. Planning is essential when flying and this was no different.

In the cruise at 36,000 feet

We got the weather reports from Vancouver center and it did not look good for us. Ketchikan was reporting winds 150@4 with five miles visibility in mist. The issues was the ceilings, they were reported at 200 feet overcast with temperature and dew-point at 9. Clearly, this would be an issue as our minimum requirements to shoot the approach would have to be 300 feet. We couldn’t even shoot the approach legally.

Mike and I looked at each other, and I looked over the approach charts. “Let’s plan on a 20 minute hold over Annette Island, inbound course is 129 degrees and looks like a parallel entry. We will go outbound on the 309 radial for two minutes make a left turn to intercept the 129 in-bound. I say we plan on holding until the weather updates in 20-30 minutes, then we can shoot the approach or go to Price Rupert. Do you have any thoughts?”

Mike was looking at the charts, “No it looks good, and I heard that Ketchikan has some good smoked salmon…also watch the terrain on both sides. I will help you with the situational awareness.”

I laughed as was the case when Mike usually spoke. “Thanks for that thought Mike, let’s try and get some smoked salmon, somewhere around here.”

I decreased the throttles to almost idle thrust and started a 2,000 feet per minute descent after receiving the descent clearance. We let Vancouver center know we were going to hold over Annette Island and that to pass it on to Anchorage Center. The information was passed on and a handoff was given to us to contact center. While in the descent, we were busy readying the airplane for arrival. Checklists were read, headings were set, and frequencies entered.

Looking out the windscreen I saw cumulous clouds forming below us around 7,000 feet or so. It was VFR on top and I saw mountains peeking through the cloud deck.

In the Cruise with increasing cloud cover

“Mike, it’s been a while since I had to hold by hand,” in a highly automated environment it’s almost unheard of to hold by hand. All that is needed to be done is to set up the computer system correctly and press the HOLD key and “abracadabra” it will hold for you. All that is needed to be done is to ensure that the plane is following the magenta line, kind of brainless this day and age if you ask me.

Mike laughed, “Yeah I do it all the time in the King Air, and it’s like riding a bike, it’s something that you never forget.”

“Do you remember when you tried to kill us in the 172 in a hold?” I said.

“Yeah, that was a bit crazy, but that was funny,” Mike was laughing.

The Dreaded Hold

Mike and I were scheduled to work on our instrument rating together. The weather was to be an IFR day with a cold front approaching over Florida. Low cumulus clouds hung low in the sky and had a menacing look to it. I was assigned the first leg and Mike would fly the second. The first leg was fine as we stayed local and just worked on approaches, holding and such. Mike was flying and I was in the backseat watching between the two seats in the front. I was trying to get a better look at the gauges and to be an alert if something went unexpected. We were getting the snot kicked out of us as the turbulence turned on the heat. Our instructor told mike to request a hold over New Smyrna beach VOR. Mind you, our instructor had the tendency to go into a daze for quite some time. Apparently, he suffered an accident a year before and was never the same. He was from South America and he carried a thick accent.

Mike called Daytona approach, “Approach, Riddle 454 requesting holding instructions at New Smyrna beach at 5,000.” We were in the soup, so there were no visual references to orient one-self to. This was serious IFR flying, all instruments. Daytona approach came back with hold instructions. As they were in the middle of reading the instructions, I saw Mike start writing down the clearance when all of the sudden we hit moderate turbulence. The pencil flipped out Mikes hands, twirling, went zero gravity and fell on the floor by our instructor’s feet.

Mike called his name, “Pete, I dropped my pencil.” Pete was staring out to infinity and not blinking. Mike tried again, “Pete.” No response was given. Mike then did the unthinkable and reached across the cockpit and was trying to grab the pencil by Pete’s feet. Unfortunately, Mike’s head was on Pete’s lap and no repose from our instructor. I could tell that Mike was searching for the pencil with his right hand on the floor. However, to try and get more leverage Mike started pulling up with this left hand on the yoke. Unbeknownst to Mike, the airplane started to climb nose-up. I heard the engine make a different sound and realized what was about to occur. The airspeed indicator started unwinding to a dangerous level.

Beeeeeeeep, a continuous noise was heard in the cockpit as the stall warning sounded. We were about to stall in IMC which can spell disaster of not corrected in a timely matter.

Pete came out of his trance, “What are jue doing!” Pete slammed the yoke forward and we instantly change attitude from nose up-to nose down. In so doing, the airplane when from positive g’s to negative g’s and anything that was not secured went floating in the air. I saw Mike’s pencil floating chest high by Pete and Mike grabbing at it.

“Jue going to kill us all!” Pete said in his accent. As we recovered from the stall, Mike

looked at Pete and said “Welcome back, where have you been?”

At that point I could not contain the laughter and adrenaline that was flowing through my system.

“Take me back to Daytona, full’ea stop!” Pete said.

Hold over Annette

The hold over Annette Island was not a dramatic, and we executed the patter with some precision. I was surprised on how well I remember how to fly the hold with the old way. It was enjoyable and satisfying.

In the hold over Annette Island

While we were in the hold an Alaska Airlines 737-800 was flying in to shoot the approach. They have sophisticated instruments and can land with lower minimums; they told us that they would let us know when they popped out of the clouds. We were in the hold for about 30 minutes now and the weather report came out to be 400 foot ceilings and 9 miles visibility. The Alaska jet landed and stated that they popped out about 450 feet.

I instructed Mike that we will shoot the approach and see what happens. I turned the airplane to 301 radial and flew it outbound.

“Mike let’s turn to the ILS frequency about 17 miles out from Annette.”

“Okay, not a problem.”

As we hit the intersection of MUSE, I rolled the airplane right to fly a 9 mile arc to intercept the ILS for runway 11.

I called “Flaps 5,” Mike moved the flap lever to the five detent. I checked my maneuvering speed and slowed using the throttles to control the speed.

“Speedbrake armed.” Mike armed the brakes for automatic deployment upon touchdown. I watch the ILS needle starting to move in. Mike stated “Localizer alive!”

I engaged the Approach mode on the autopilot and watched the airplane start intercepting the course.

“Gear down, flap 15,” I called. Mike complied as he dropped the gear I noticed a loud rushing noise and felt the drag kick in as we slowed even further.

“Flap 25, glide slope alive.” I took the autopilot off line and put my hands on the yoke. I wanted to feel the jet and how it responded to control inputs. Mike silenced the autopilot alarm, “Flap 40, landing checklist.” Mike put the flaps to the commanded position and read the checklist.

“Gear?”

“Down, three green.” I stated.

“Flaps?”

“40/40, green light,” as I looked at the flap indicator.

“Speedbrake?”

“Armed,” after checking the position.

“Landing checklist complete,” Mike said.

Our airspeed was on target and I was tracking the glideslope okay.

“1,000 feet,” Mike called.

I was concentrating on the gages as we were now in complete IMC with no outside references. Mike transition to the radar altimeter and stated “500 feet, looking outside.” Mike started looking up to see if he can visually make the runway environment. “Got a visual!” Mike said.

I looked up and said “Going outside,” Mike went heads down just in-case I lost visual contact of the runway. Mike would be flying the missed approach if we needed to from this point on.

I saw the runway about 300 feet of altitude, it was just enough time for me to state, “Landing!” and start flaring the airplane to arrest the descent rate. I cut the throttles at 20 feet and landed firm. I pulled up the thrust reversers and Mike stated “Speedbrake up, reverses out.”

Stopping performance on the -200 is amazing. This airplane was built for short runways and it showed. The airplane came to 40 knots in a few seconds. I taxied down the runway and slowed to turn the airplane. Mike cleaned up the flaps and speedbrake and shut the landing lights off. I exhaled out loud and said “Holy cow, that was intense and something I am not used to doing in the states that often.” We taxing down a slopping taxiway ramp to the cargo terminal, shut down the engines and I looked at Mike.

Taxing off Runway 11 in soupy conditions

Mike looked at me, took the headsets off and said “I am going to get me some salmon,” completely unfazed. I slumped over the yoke.

Tuna-

Comments